Massachusetts enacted one of the most progressive school discipline laws in the country in 2014 that aimed to stop schools from pushing out kids for often minor transgressions.

Ruby is a bright, charming girl.

But the senior at Salem Academy Charter School admits she has trouble reining in her emotions, a shortcoming that has resulted in fighting and defying teachers.

In fifth grade she flipped a chair in frustration.

"And that was that. I was suspended," said the 18-year-old, who asked that NBC Boston not use her last name.

She is one of the tens of thousands of students who get suspended each year from Massachusetts schools.

In 2014, Massachusetts enacted one of the most progressive school discipline laws in the country that aimed to stop schools from pushing out kids for often minor transgressions, known to advocates as the school to prison pipeline.

"We know that kids who are suspended are more likely to drop out," said Elizabeth McIntyre, the Equal Justice Works Fellow at Greater Boston Legal Services. "We know that kids who drop out are more likely to be arrested before they turn 18. We know that kids arrested before they turn 18 are more likely to get arrested again before they turn 18."

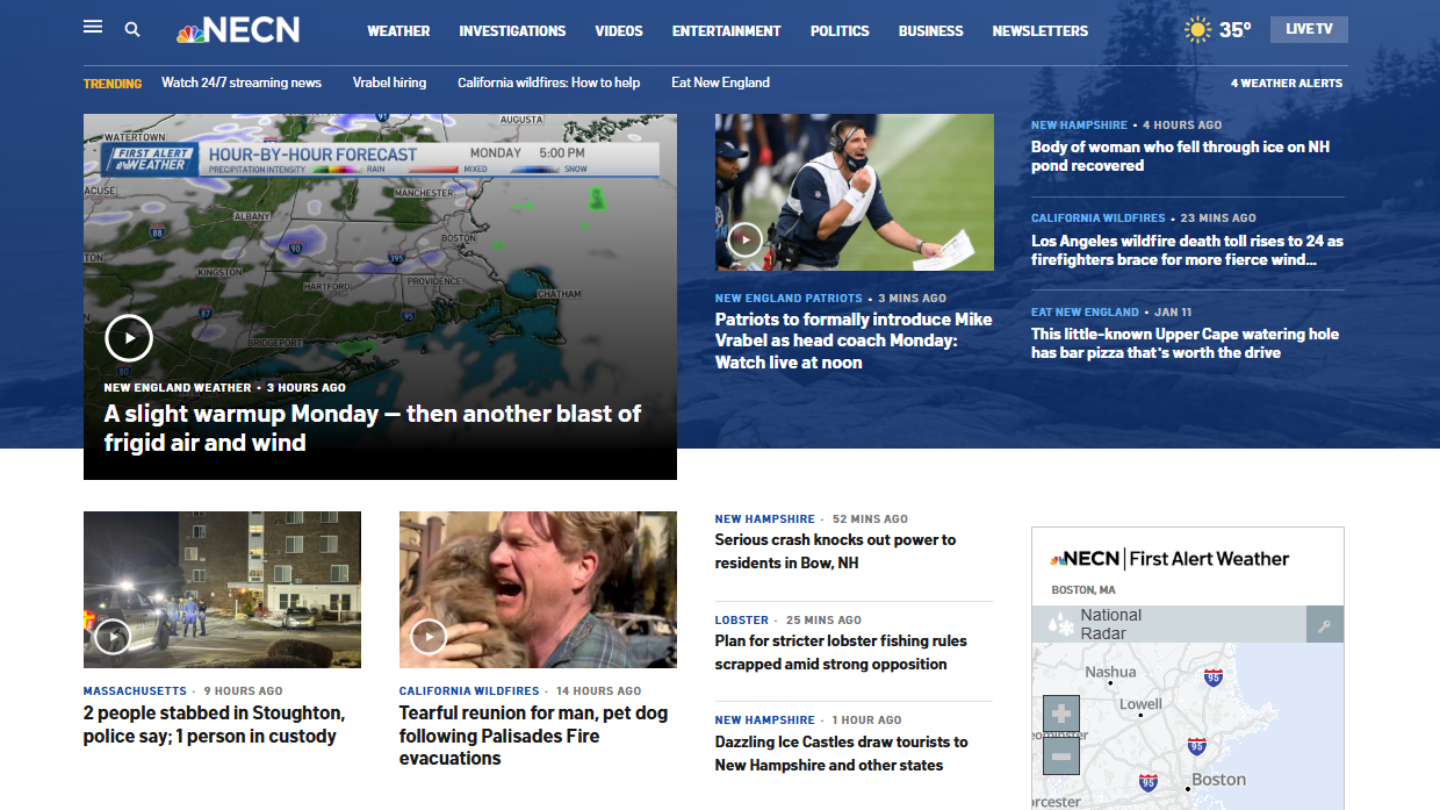

Local

In-depth news coverage of the Greater Boston and New England area.

Compounding the problem is kids of color are suspended at disproportionate rates.

According to state data, last year black students – at 93 kids suspended per 1,000 students -- were suspended nearly 3.5 times more often than white students, who were suspended at a rate of 27 per 1,000.

Hispanic and Latino kids -- 77 per 1,000 – were suspended almost three times as often, and kids with disabilities twice as often as their non-disabled peers.

"It pushes kids behind academically," McIntyre said. "It pushes kids away from their school communities."

And by most accounts, the law is working. Since it was enacted, 10,000 fewer students have been suspended or expelled -- a 20 percent reduction.

But advocates say some schools send kids home for disciplinary issues, a sort of off-the-books suspension that the school does not record.

The law requires that when kids are suspended, the school notifies the child’s parent, schedules a suspension hearing, and, in some cases, offers tutoring, services or an alternative school setting.

But Ruby was suspended last year for trying to start a fight and claims she wasn’t offered any protections, like paperwork, a phone call to her mother or a hearing.

"I didn’t know about any kind of rights, I don’t know the process," said Ruby’s mother, Rita.

Salem Academy Charter School would not comment specifically on Ruby’s case, but said in an email, "We have been scrupulously careful in the past five years to ensure due process for any student accused of a significant breach of conduct."

If schools are keeping the discipline off the books, there is no data to prove how often it’s happening.

McIntyre said she has more than 150 student clients who say they've been suspended without due process. It’s gotten so bad, she now tells kids to keep her card in their pocket.

Mitchell Chester, commissioner of the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, said he’s heard about "off-book" suspensions and calls them "a problem," but can't say how widespread they are.

"We need to always be on guard for unintended consequences," he said. "Hopefully it's not a pattern."

The agency identified and put on notice who they call three dozen or so "outliers" -- schools with suspension and expulsion rates so high – the department has stepped in to offer training and peer mentoring to reduce their rates.

Chester said, "Why are you suspending at this rate? Is this an issue of one or two teachers within the school who are struggling and rely on suspension/expulsion or across the school or is this endemic across the school?"

Chester promised to investigate any claims of off-the-books suspensions that come to his department, and said he would hold superintendents accountable. McIntyre, with Greater Boston Legal Services said, in most cases, what she contacts the school, the problem is typically resolved, but she hopes to see change system-wide, not just school-by-school.

Ruby, meanwhile, has seen friends drop out of school after suspensions. But she plans to make it to college.

"I was not willing to let anything affect me and I was not willing to give up," she said.