In late March, Ron Marlowe was still commuting to work on public transportation, and like most others, he wasn't wearing a mask.

Then one day, Marlowe came down with an incredible headache. He tested positive for COVID-19 and spent five days in the hospital.

"They put me in a wheelchair and they whisked me away," he remembered.

Marlowe says he made choices that, in retrospect, put him at risk. But he also lives in Randolph, which has one of the highest COVID-19 rates in Massachusetts.

Randolph is also one of the most diverse communities in the state. Marlowe says he's not blind to new data that shows people of color are at increased risk from the disease.

"COVID is a disease of circumstance," he said.

As the state eases more COVID-19 restrictions, advocates like Marlowe, a member of the Black Boston COVID-19 Coalition, say the state must do more to protect communities of color.

Data released in June shows Black and Hispanic people in Massachusetts are getting COVID-19 at rates three times higher than whites.

And in nine of the 10 communities with the highest infection rates, people of color make up more than half of the population, according to the state Department of Public Health.

"It's hard to feel like you're not seen, or you don't matter, or you're less important," Marlowe said.

Coronavirus Case Count and Massachusetts’ Population

This map plots weekly coronavirus case totals on top of census tract data showing the percent population non-white, housing density and median household income of a given area. Click or tap for more information.

Sources: Massachusetts Department of Public Health Weekly COVID-19 Public Health Report; American Community Survey 2018. Note: Percent non-white refers to the members of the population who are classified as non-white, e.g. Black alone, or Hispanic. For more information about how the Census Bureau defines race and ethnicity, see here.

Amy O’Kruk/NBC

Health experts say the reasons behind the higher case rates vary, but they're rooted in long-standing racial inequities exposed by the pandemic.

People of color make up a majority of the workforce in many essential industries, and many rely on public transportation to get to work.

They're also more likely to live in densely-packed areas and multigenerational housing. And housing segregation is linked to health conditions like asthma that put you more at risk of severe illness or death if you contract COVID-19.

Carlene Pavlos, who heads the Massachusetts Public Health Association, says the Baker administration mishandled its early response to racial disparities in the pandemic, and communities of color have paid a price.

"They are sick and dying at higher rates," she said. "That is not fair. It's not just and we're not going to stand silently by."

The association is part of a coalition of nearly 100 community organizations calling for the state to enact stronger precautions so that no group is disproportionately harmed by the pandemic.

More on coronavirus

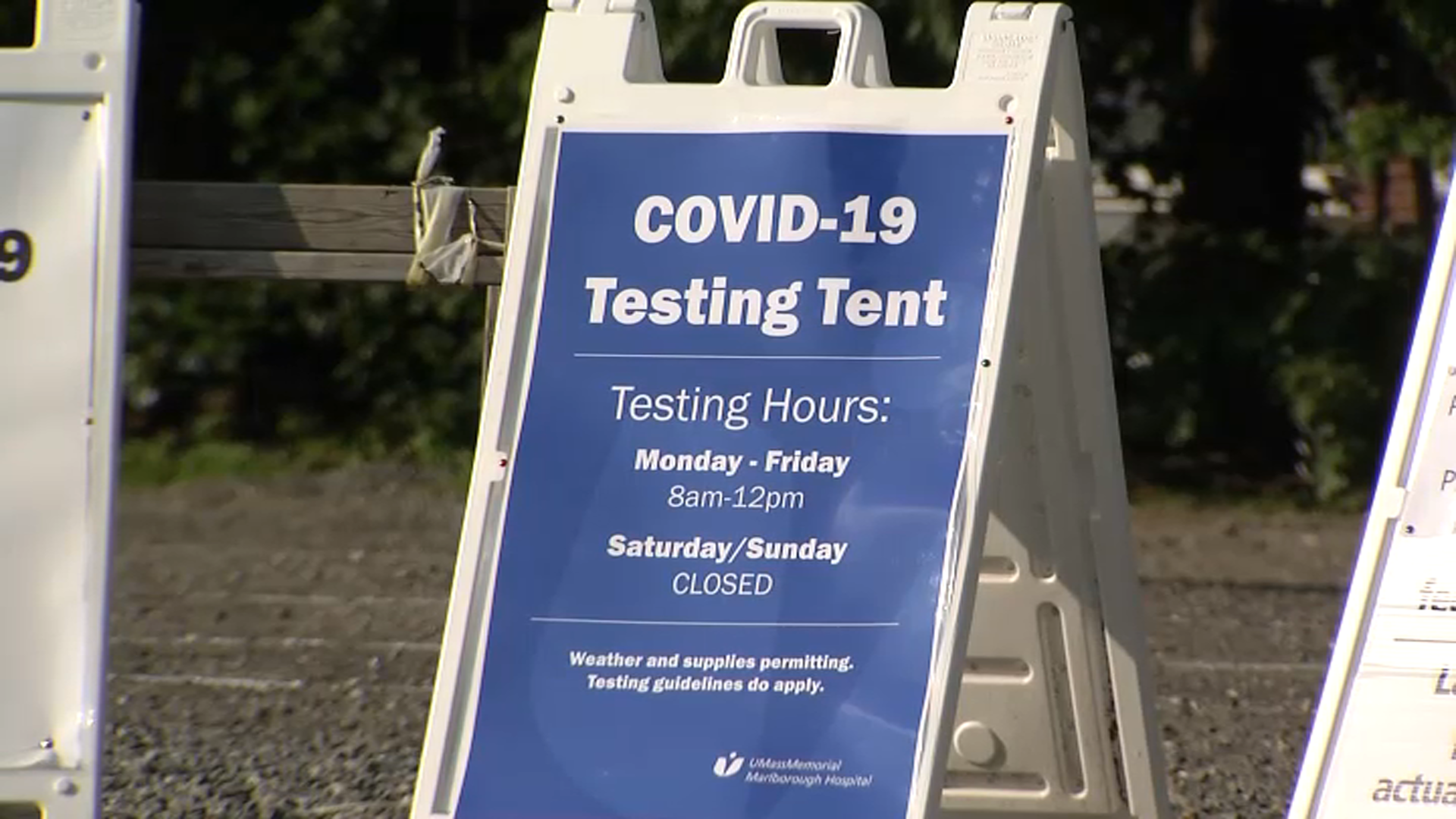

A new initiative launched this week will address one of the major shortcomings they've highlighted in the state's response – lack of access to testing.

Gov. Charlie Baker on Wednesday said his administration will offer free tests in eight communities experiencing higher infection rates: Chelsea, Everett, Fall River, Lawrence, Lowell, Lynn, Marlborough and New Bedford. New testing sites will be opened and mobile testing vans will be deployed beginning Friday and continuing through early August.

The state also assembled an equity task force to study COVID-19 disparities. It previously recommended distributing more personal protective equipment to essential workers, stabilizing housing and doing more outreach in multiple languages.

It also called for collecting better data on COVID-19 cases. But the coalition of public health and advocacy groups say that effort comes too late.

Despite a state mandate in April to collect race and ethnicity information from all COVID-19 patients, that information is still missing in one third of the state's 110,897 recorded cases.

"Without understanding what people in what communities are at highest risk, we can't put into place prevention strategies," Pavlos said.

Louis Elisa, a former regional director for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and a member of the Black Boston COVID-19 Coalition, said the bottom line to be drawn from the numbers is that people of color are disproportionately suffering severe illness and dying.

And while reopening the economy is important, it can't be done on the backs of the people suffering the most, he said.

The Public Health Association and others issued a list of recommendations they want the state to address as businesses reopen and more people resume their pre-pandemic routines.

Among other things, they want the state to track more granular data about who is getting sick, such as income, disability status, and primary language, to get a better sense of who is being most harmed.

They also want the state to steer more resources to enforcing workplace safety protections. Those duties fall now to local boards of health, many of which are understaffed, and the state Department of Labor. Advocates say those groups can't ensure workers are safe on the scale necessary.

They also want the governor to give people of color more seats at the table and engage groups that stand to be most harmed by reopening decisions. They propose establishing a Recovery Advisory Board to advise the governor.

"We are willing to do the work necessary to protect our community," Elisa said. "To make sure that we have equal access to the resources, we just need the support."