- Digital tools have made it easier to find reproductive health care information, but also created new legal risks for those who use them.

- Prosecutors have already used search and text histories as evidence against women who claimed to have lost their pregnancies in miscarriages.

- There are several ways consumers can better safeguard the information they share online.

After last month's Supreme Court ruling reversing Roe v. Wade, the landmark decision protecting the legal right to an abortion, many people looked to the early 1970s for what life without the long-standing precedent would look like.

WATCH ANYTIME FOR FREE

Stream NBC10 Boston news for free, 24/7, wherever you are. |

But accessing abortions is much different in 2022, thanks in large part to technological innovations, including safe medication used to induce abortion.

There are also new digital tools that can connect people with medical providers, friends and other resources, making it much easier to find information about accessing abortions.

Get updates on what's happening in Boston to your inbox. Sign up for our News Headlines newsletter.

With the reversal of the landmark ruling, many people are asking for the first time whether digital tools they use may put them or their loved ones at risk. Since the U.S. and most states lack digital privacy laws to safeguard consumer information, it often falls on companies and consumers themselves to protect their privacy online.

Here's what to know about how digital tools collect data, how prosecutors may seek to use such information in abortion and pregnancy-related cases and how consumers can be more mindful about the data they share.

How digital tools collect and use your data

Money Report

Digital tools can collect your data in a variety of ways that can usually be found in their privacy policies. These often dense legal documents will tell you what types of data a given tool will collect on you (name, email, location, and so on) and how it will be used.

Consumers can look for words like "sell" and "affiliates" to get a sense for how and why their information might be shared with other services outside of the one they are using directly, as The Washington Post recently suggested in a guide to these documents.

Some web pages might track your actions across the internet using cookies, or little snippets of code that help advertisers target you with information based on your past activity.

Apps on your phone may also collect location information depending on whether you've allowed them to in your settings.

How to protect your information

The best way to protect any sort of information on the internet is to minimize the amount that's out there. Some providers have recently taken steps to help consumers minimize their digital footprint when it comes to reproductive health care.

Google said last week it would work to quickly delete location information for users who visit abortion clinics or other medical sites. It will also make it easier for users to delete multiple logs of menstruation data from its Fitbit app.

Period-tracking app Flo recently added an anonymous mode that lets users log their menstruation cycles without providing their names or contact information.

But it's largely still up to consumers to safeguard their own information. Here are some ways users can protect the information they share online, whether it is related to health care or not, based on tips from digital privacy experts like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Digital Defense Fund:

- Use an encrypted messaging app such as Signal to communicate about sensitive topics and set the messages to erase themselves after a set period of time. This means getting others in your network onto the same app as well.

- Turn off or limit location services on your phone to only the apps that it's necessary for while you are using them.

- If you're visiting a sensitive location, consider turning off your phone or leaving it at home.

- When searching online about sensitive topics, use a search engine and browser that minimizes data collection, such as DuckDuckGo, Firefox or Brave.

- Use a private browsing tab so your website history won't be automatically saved.

- Use a virtual private network to conceal your device's IP address.

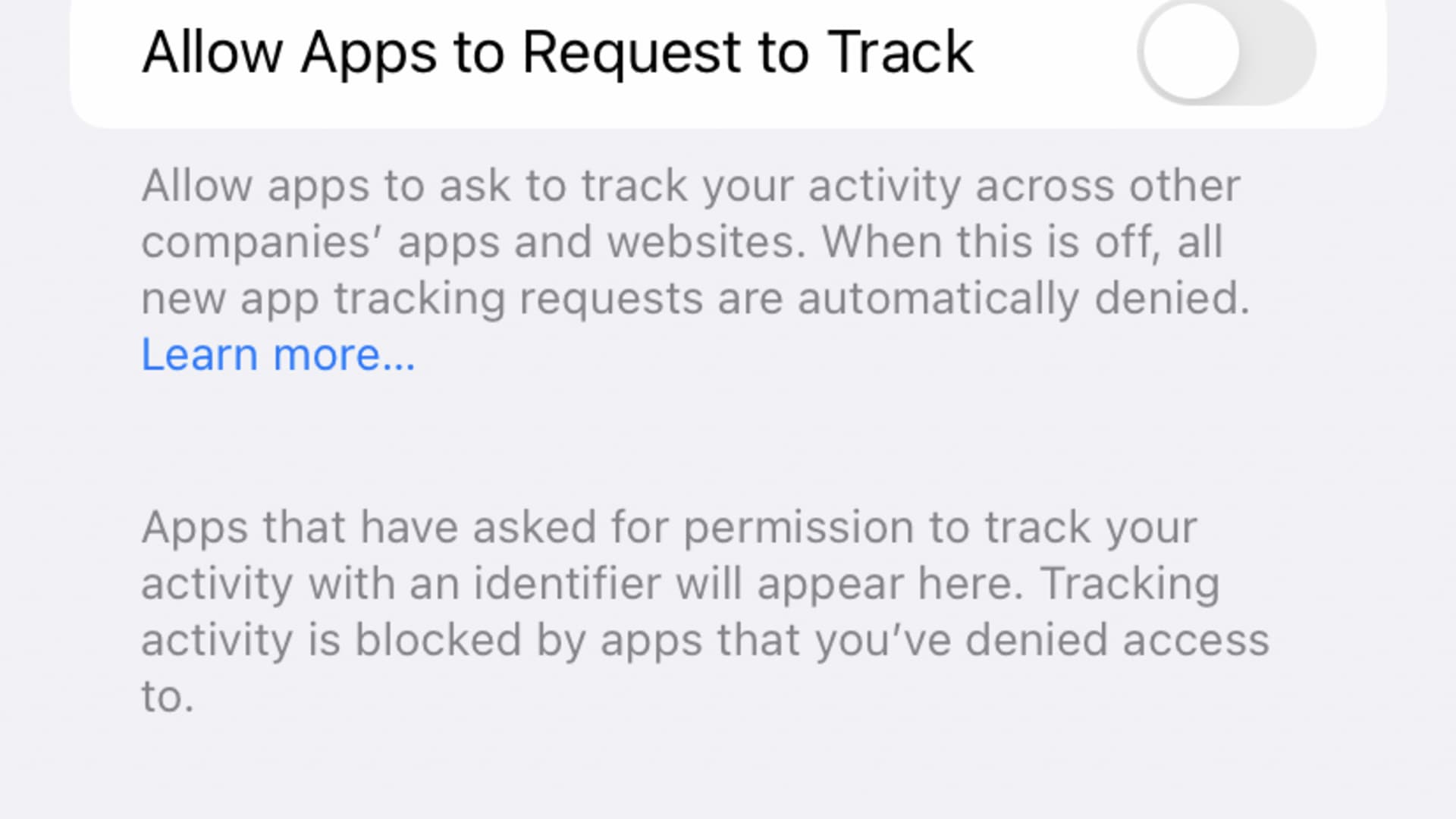

- Disable your mobile ad identifier that can be used by third-party marketers to track and profile you. The EFF has step-by-step instructions on how to do this on Google's Android and Apple's iOS.

- Set up a secondary email and phone number, like through Google Voice, for sensitive topics.

How data could be used in court

The risks of digital tools being used by prosecutors in cases involving abortion or pregnancy loss are not theoretical.

In at least two high-profile cases in recent years, prosecutors have pointed to internet searches for abortion pills and digital messages between loved ones to illustrate the intent of women who were charged with harming babies they claimed to have miscarried.

Those cases show that even tools that are not directly related to reproductive health care, such as period-tracking apps, can become evidence in an abortion or pregnancy loss case.

It's also important to know that law enforcement may try to get your information without accessing your devices. Prosecutors may seek court orders for companies whose services you use or loved ones you have communicated with to learn about your digital whereabouts if they become the subject of a legal case.

WATCH: Tech companies and execs weigh in on Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade