The rising daily coronavirus case count in Massachusetts isn't the only warning sign of a new spike in cases for the Boston area.

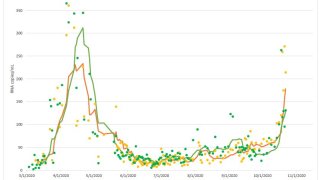

Traces of COVID-19 are appearing more frequently at the sewage plant that treats wastewater for Boston and many of its suburbs, according to public data shared by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority.

Sewage from the southern and western suburbs whose water is treated at Deer Island Treatment Plant has levels coronavirus not seen since last April, when the virus was still near its peak, according to the latest data. The northern suburbs' sewage is showing less virus so far, but it's not far behind, and both lines are trending up.

The information comes from a pilot study and is meant simply as a tool to track the pandemic in the area. But Ashish K. Jha, the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, said on Twitter Saturday that watching the data has left him "more and more concerned."

That's because, unlike coronavirus cases -- which are detected when people get tested -- COVID-19 data from sewage should measure how prevalent the virus is in the community at large, including among people who don't have symptoms and don't get tested, since the virus they shed through body waste would contribute to levels found in sewage.

The wastewater spike comes amid fears that Massachusetts is beginning to experience a new surge in cases, something being seen across the country.

"It's more evidence of us seeing a second wave," Boston University global health and medicine professor Davidson Hamer told The Boston Herald.

The U.S. has set new records in coronavirus cases detected on successive days this week, and on Saturday and Sunday, Massachusetts reported more than 1,000 new coronavirus cases, numbers not seen since May.

There's data that suggests the wastewater data like the graph above could show the scale of the pandemic sooner than contact tracing.

A Yale study published in September found that wastewater data in New Haven showed "very similar" trends to what contact tracing found, but about a week earlier, NBC News reported.

Earlier this month, MIT announced that it would begin testing wastewater on seven buildings on campus to see if it's an effective way to track the virus and keep students, faculty and staff safe.

“It makes a lot of sense when you think about the fact that there’s a lag between the time somebody gets sick and starts shedding the virus, and the time when they’re symptomatic enough to seek care and get a clinical test,” research scientist Katya Moniz said in a news release.

The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority said in June that it awarded a $200,000 contract for the Deer Island Treatment Plant wastewater study "as an early warning system tracking trends and potentially predicting a second wave of COVID-19."

Forty-three communities from eastern Massachusetts, have their water treated at the plant, including Boston, Cambridge, Framingham and Quincy. Together they have accounted for 40-50% of Massachusetts' coronavirus cases, the agency said in its June announcement.

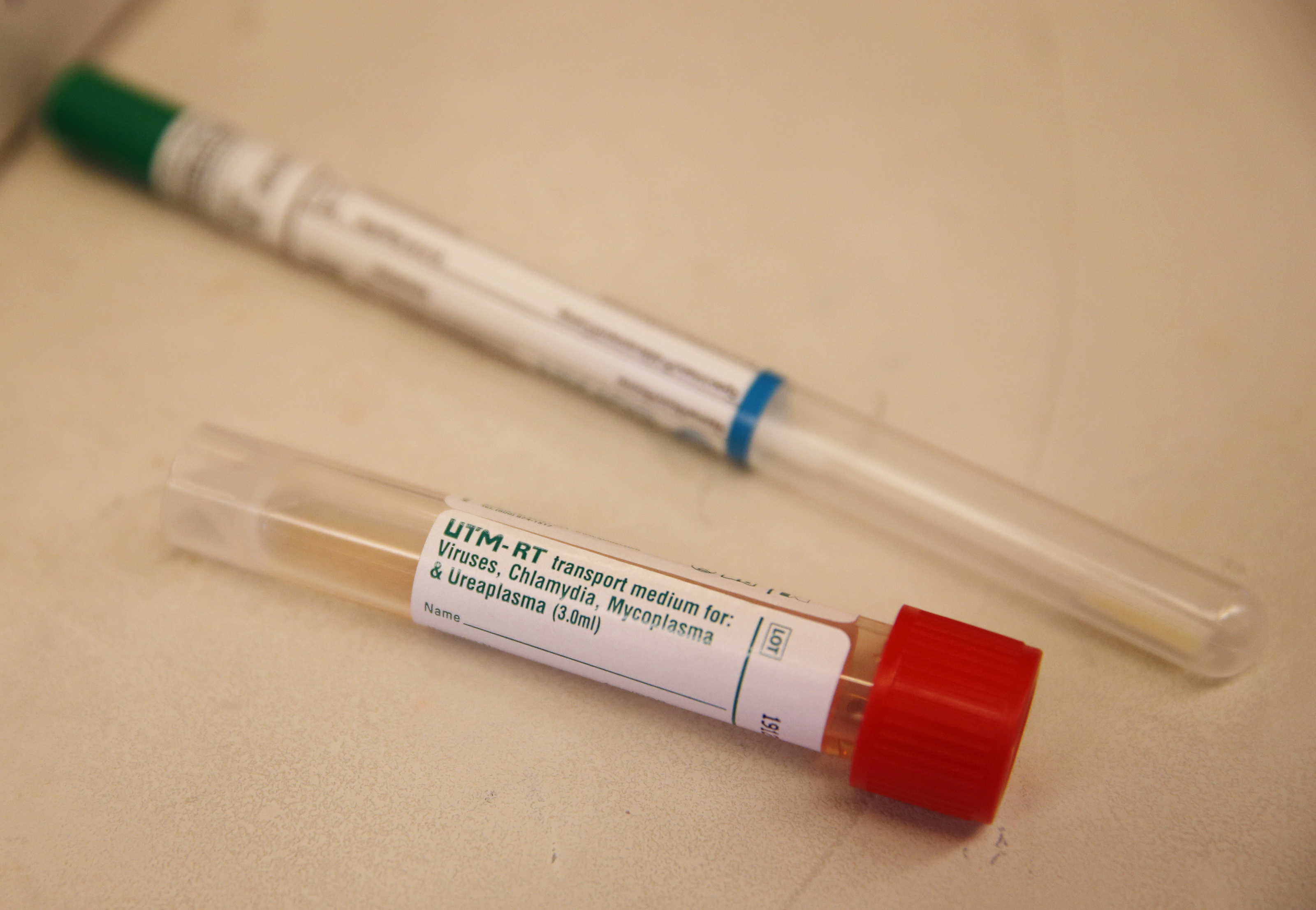

Three times a week, water from the northern and southern sections of the coverage area is tested for viral RNA -- genetic code -- from the virus. If the pilot program is successful, the study would likely be extended for the rest of the pandemic, according to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority.