At 6:30 on a recent Friday morning, Kurt Curry leaves his South End apartment in Boston, a disposable white mask on his face.

He walks in beige cargo pants and a blue button-up shirt to the Symphony T station on the Green Line, making sure to keep six feet from anyone he encounters on his way.

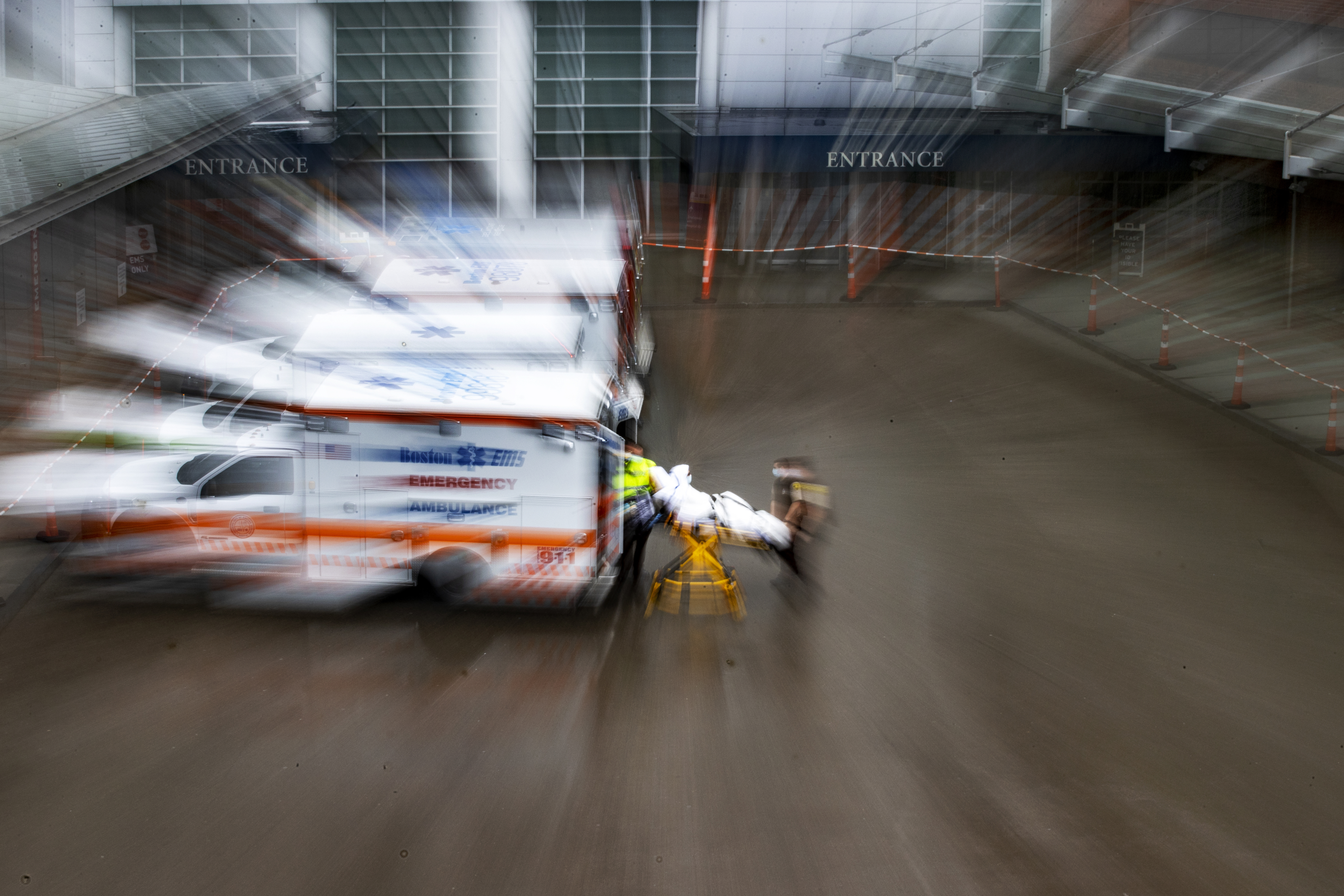

The train brings him to Longwood, where he's been fighting against the new coronavirus in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit of Boston's Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center since March.

Curry is one of 321 housekeepers in the Environmental Services Department who clean, sanitize and take out the trash at the hospital, making sure it's a safe environment for patients and nursing staff.

His new normal is an eight-hour routine that he says he's now used to and that, despite the pandemic, he considers a "blessing."

"I feel needed. I know I'm needed," says Curry. "When I go to work, I have people [saying] 'Kurt, Kurt, Kurt.' People are constantly needing me, and asking me for assistance, to take care of something that they can't."

Like doctors and nurses, who are often the most prominently celebrated essential workers, housekeepers, janitors and other cleaning service workers are on the front line of the fight against COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus that has killed more than 5,800 people in Massachusetts, the third-highest death toll in the United States.

"I don't think a lot of people think about housekeepers and [Environmental Services Department] staff," Curry says. "We seem to be kind of in the background, but we're not, we're up in the front. We're working with the staff. We're working with the nurses and the patient care technicians. Right along with them."

Hospital custodial staff is exposed every day to any kind of airborne illness the same way the medical staff is, says Kristine Viale, operations manager of the department.

"The medical staffs aren't the only ones risking their lives," Viale says. "Environmental Services workers are beyond important, they are essential. If our environment isn't properly disinfected and cleaned, then the virus could run rampant in our facility and get not only ourselves but our patients."

Many Massachusetts hospital systems have reported that employees are testing positive for the coronavirus. As of Friday, 336 employees in the Beth Israel Lahey Health system, which includes Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, were not working because they'd tested positive for the coronavirus, according to Jennifer Kritz, a spokeswoman for the system. Still more have tested positive and returned to work already.

Kritz didn't detail what departments those employees worked in, and couldn't say whether they were exposed in the community or in the workplace. While some hospital workers' unions are pushing for hazard pay, Kritz said the system is not considering that or pay increases at this time.

The contributions of custodial staff aren't always overlooked. At an April 29 news conference, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh made a point to recognize hospitals' cleaning staffs for taking on "some of the most daunting and necessary work in our city right now."

To show what that work is like, we spoke with five people who do custodial work at four Beth Israel Lahey Health hospitals around Massachusetts.

The New Routine

Curry's shift starts every day at 7 a.m. It's supposed to last until 3:30 p.m., but he never knows when he'll be out because he wants to make sure he thoroughly cleans every patient's room he visits.

Once the 48-year-old arrives at the hospital, he changes his clothes and puts blue scrubs on, so he isn't carrying microbes from outside into areas where patients are located.

Geared up with an N95 mask, gloves, goggles and a yellow gown, Curry grabs the trash bags he needs and a mop. He is ready to flow from room to room in what has become a more hectic, busier schedule than before the pandemic struck.

"I used to take trash in the [ICU] and the patient rooms two times a day," he says. "Now I'm up to four times a day."

In the rooms, he empties four different containers: a laundry bag, another laundry bag just for gowns, a red biohazard bag that contains fluids or dangerous materials and a sharps box where needles are usually trashed. Once all the trash bags are changed, Curry wipes and sanitizes all the touch areas, things like door handles, light switches, telephones, computers. At last, he mops the floor.

"I am definitely on the front line and I do look at it as a battle," says Curry, who has been working at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center since 2017, a year after moving to Boston from Illinois. "The enemy is the bacteria, it's the virus and the virus is everywhere. I know that what I'm doing with my cleaning not only creates a clean environment ... it makes for a safe environment as well."

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center has the second-highest number of COVID-19 patients in the state. As of Monday, the hospital was treating 164 patients, 71 of which were in intensive care units, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

There are moments when things can get "really crazy," Curry says, but an anthem of hope often plays over the loudspeaker at the hospital: "Sweet Caroline." The song echoes in the hallways when a patient has recovered from COVID-19 and is able to go home. It played three times in 15 minutes on May 7, he recalls.

"It was one song, again and again," Curry says. "And you just knew that people were on their way out and that they were well enough to go home. And that was motivating."

Out of a 'Scary' Situation, New Lifestyles

While cleaning at Winchester Hospital, housekeepers Hanane Benjiya and Jocelyn Morales think about their families, how to protect them as much as how to care for them.

As of Monday, Winchester Hospital had 26 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, one of whom was in an ICU bed, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Benjiya, 37, has been working in the Environmental Services Department since 2015. The units where she works were the first ones at Winchester to receive COVID-19 patients back in March.

"I was off that day when I heard that we started receiving patients with COVID-19," says Benjiya, who is originally from Morocco. "I was like, 'Oh, so it's really true. It's gonna happen.'"

Morales, who normally works in a different unit of the hospital, says she got used to the new normal. Even if at the beginning it was "rough" and she "was scared to enter in a COVID-19 unit," she keeps going because she feels "they are making a difference."

"It's important, we're important now," says Morales, who is originally from Puerto Rico. "We have to be here, we have to clean."

Morales' and Benjiya's family members are always in their thoughts. Both the housekeepers strictly follow the guidelines provided by their hospital, wearing scrubs and other personal protective equipment in the coronavirus units, washing their hands frequently and changing their clothes.

Get top local stories in Boston delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC Boston's News Headlines newsletter.

But the fear of bringing the virus home is constantly with them.

Their lifestyle has changed radically since the beginning of the pandemic. Even time for hugs has changed.

Benjiya, whose husband Said works at Winchester Hospital as well, has their 7-year-old-son Rayan waiting for her at their home in Winchester. Back when life was normal, Rayan would have gotten a hug from his mom as soon as she walked through the front door. Now, Benjiya has to go through the backyard to the basement, shower there, put all her clothes into the laundry and only then hug her son.

"I'm worried if I bring it to my son," Benjiya says. "If I go to the front door, my son sees me and he jumps on me, hugging me. I don't want that to happen. So that's how I try to protect him."

Morales, who lives in Lowell with her husband Edison, shares Benjiya's fear. She has come up with a new routine, spraying her shoes on the front door of her home and putting all her clothes in a paper bag before having a shower.

"It was scary at first, I can't lie. It was scary," she says. "Now it is becoming a lifestyle. I always keep a positive mindset. Praying to God has given me strength every day to wake up and just give it my best out there."

Working as a Team

While Benjiya and Morales juggle cleaning coronavirus-infected rooms at Winchester Hospital and protecting their families from the virus, John Silva tries to protect his staff at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge.

Silva, director of both the environmental services and patient transport departments, has been working at Mount Auburn Hospital for 16 years. While his responsibilities are administrative, once he is done with his daily duties, he changes his clothes and gears up with PPE to clean alongside his staff on the front line.

"There are no options here. You have to stay in the fight," Silva says. "This virus doesn't take time off. We're here 24 hours, seven days a week. The virus is here and we're gonna keep fighting until it's gone."

Mount Auburn Hospital on Monday had 35 coronavirus patients hospitalized, seven in ICU beds, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Silva, who is 58 and hails from Dorchester, manages about 100 people. He helped train his staff before the pandemic exploded in Massachusetts so they could be more comfortable with the situation, but says one of his preoccupations is to make sure no one on his staff gets sick and that everyone has enough scrubs and protective gowns.

"I'm sending them to the front lines, and that is a little unnerving," Silva says, his voice trembling. "That's why I want to be next to them, because I don't expect anybody to do anything that I wouldn't do myself."

It's a fight that Kim Malios is experiencing every day. She is a housekeeper at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital in Plymouth, where 65 people were hospitalized with COVID-19 as of Sunday, eight in ICUs, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Malios, 43, works on the hospital's coronavirus floor. While her job is busier now, and different, with "so much protective gear, excessive cleaning and steps" to follow, she says her relationship with her co-workers has strengthened.

"There is a sense of accomplishment that we work together so closely as a team and everybody supporting one another," says Malios, who is from Plymouth and has been working there for 15 years. "We are holding each other together."

Once her shift is over around 3:30 p.m., she leaves the hospital and takes the 8-minute drive that will bring her back home to her 7-year-old twin boys, Loukas and Matthaios, and her 10-year-old daughter Efthemia.

Around the same time, Curry's shift is close to its end at Beth Israel Deaconess in Boston. He goes to the changing room, takes off his scrubs -- they'll be washed that same evening -- takes a shower and puts the uniform he wore on his way to work back on.

As he commutes home to the South End, he thinks back on the day he had and if he did everything on his daily schedule. He reminds himself that this crisis will come to an end and, hopefully, that we will have learned from this pandemic.

"I think people have taken a lot for granted. And I see that people appreciate things a lot more now," Curry says with a smile. "Hopefully they will look at somebody in my position and appreciate me in a different way."