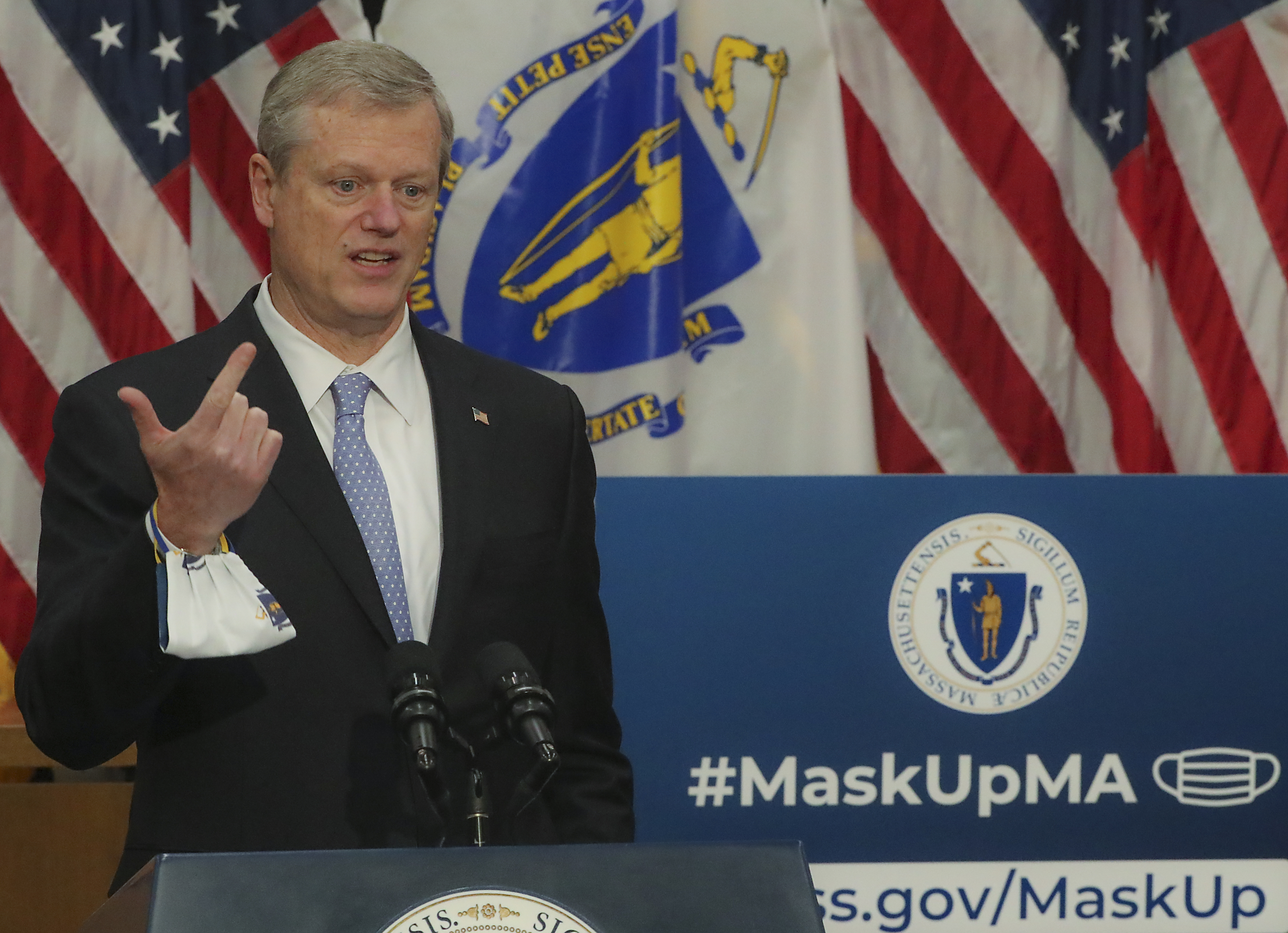

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker returned a police accountability bill to state lawmakers Thursday, asking for changes before he can sign the legislation.

A key element of the long-debated bill is the creation of a civilian-led commission to standardize the certification, training and decertification of police officers.

Baker had wanted the commission to be part of the administration under the Executive Office of Public Safety. The Legislature's bill would instead create an independent commission. Baker said he can accept that change, provided the tasks given to the commission are achievable and it has the resources it needs.

In a letter to lawmakers dated Thursday, Baker praised the bill overall, but said there are elements that "introduce barriers to effective administration and the protection of public safety without advancing the central goal of improving police accountability and professionalism."

More on the police reform bill in Massachusetts

Baker said he opposes the bill's moratorium on facial recognition technology. Baker said the use of facial recognition helped convict a child rapist and an accomplice to a double murder in recent years.

Baker also opposes a portion of the bill that would move oversight of the existing Municipal Police Training Committee from the Executive Office of Public Safety to the bill's proposed civilian-majority Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission.

"I do not accept the premise that civilians know best how to train police," Baker said.

The bill also needs a clearer definition of what it means by "bias-free policing," he added.

Baker is wrong about police use of facial recognition technology, according to Carol Rose, executive director of the ACLU of Massachusetts. She said the bill is designed to protect residents from the unregulated police use of the technology which she said unfairly targets Black and brown people.

"Unchecked police use of surveillance technology also harms everyone's rights to anonymity, privacy, and free speech," Rose said in a written statement Thursday.

The 129-page bill failed to pass the Massachusetts House by a veto-proof majority, possibly weakening the leverage of Democratic leaders in negotiating with the Republican governor.

Baker, who filed his own police accountability bill in January, said he won't sign the bill unless lawmakers address his concerns.

The Legislature's bill would also ban the use of chokeholds, limit the use of deadly force, and create a duty to intervene for police officers when witnessing another officer using force beyond what is necessary or reasonable under the circumstances.

The House voted 92-67 to approve the final bill. The Senate approved the bill on a 28-12 vote.

Senate President Karen Spilka and House Speaker Robert DeLeo, both Democrats, said in a joint statement when the legislation was unveiled that it represents "one of the most comprehensive approaches to police reform and racial justice in the United States since the tragic murder of George Floyd."

Under the bill, the Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission would serve as the civil enforcement agency to certify, restrict, revoke, or suspend certification for officers, agencies and academies. It would also be able to refer cases for criminal prosecution and report annually to the Legislature, governor and the attorney general.

The commission would also maintain a publicly available database of decertified officers, officer certification suspensions, and officer retraining.

The bill has received fierce pushback from police unions.

The State Police Association of Massachusetts said in a statement that the bill "creates layers of unnecessary bureaucracy and costly commissions staffed by political appointees with no real world experience in policing and the dangers officers face every day."

The bill would also make clear that qualified immunity would not extend to a law enforcement officer who "violates a person's right to bias-free professional policing if that conduct results in the officer's decertification."

Efforts to limit qualified immunity -- which largely protects police from being civilly liable for excessive use of force -- have also come under criticism from police unions.

Democratic U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley hailed portions of the bill after lawmakers passed the measure, including the ban on chokeholds and limits on no-knock warrants, but said more needs to be done.

The legislation is in part a response to statewide demonstrations following the May 25 killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer.