The prison population in Massachusetts has plummeted over the last decade — so much so, that the Commonwealth now boasts the lowest imprisonment rate in the country.

WATCH ANYTIME FOR FREE

Stream NBC10 Boston news for free, 24/7, wherever you are. |

But what's behind the change?

There's not a single, straightforward answer. But in this latest Wider Lens segment and report, we take a deeper look at how changing attitudes toward incarceration, crime and corrections are changing lives.

Get updates on what's happening in Boston to your inbox. Sign up for our News Headlines newsletter.

Take Antwan Ramos, of Haverhill, for example.

He was sitting in a jail cell in October, when his lawyer shared with him some surprising news.

"He gave me the option either to stay in jail or to come home and take this program," Ramos said.

That was how Ramos was introduced to one of the state's Community Justice Support Centers, which offer therapy, job training, drug screening, education and more.

Ramos said it's altered the course of his life.

"It was a lot of inner work that I really want to be doing on myself, so that I can deal with society, so that I can be in society and be a good citizen," Ramos said.

Focusing on rehabilitation, judges have been sending more people on probation or pre-trial to these centers, which are coordinated by the state's Office of Community Corrections.

But what's driving a historic drop in prison populations? Researchers and public officials point to a number of factors, including crime prevention, treatment and better re-entry support.

The data speaks for itself.

Massachusetts' average daily prison population in 2023 was 6,070. That was about a 45% decrease from 2014, when the average daily population was 11,034.

"We still have to hold people accountable, but we're holding people accountable in different ways," Undersecretary at the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security Andrew Peck said.

Peck's office oversees the Department of Correction.

"Those declining populations are directly related to a lot of the good work that's been done both in the department and upstream, I like to say," Peck said. "So a lot of changes, in how how police departments engage with their communities and they're taking very creative and innovative strategies, to become problem solvers in the community."

Corrections, Peck said, is a changing field — one that is becoming more humanized, with added emphasis on finding the right kind of accountability for each individual.

"My perspective, we should have the smallest correctional footprint possible," Peck said. "If we have to incarcerate someone, they should be the right person. So I think that's one thing that Massachusetts has gotten right. As opposed to a lot of other states. We hold people accountable, but we understand that there are different pathways to that accountability, and we don't have to incarcerate someone to hold them accountable."

For those who are incarcerated, Peck said that efforts to incorporate education, substance abuse treatment and housing aid upon release contribute to a low recidivism rate in Massachusetts, which is another factor said to be driving down prison populations.

"The benefit of having the reduced population is we can actually spend and concentrate more time and attention on people's needs, and create a safer, healthier environment," Peck said.

A recent study from the Department of Correction showed that people were less likely to reoffend when they were provided services they needed like substance abuse treatment and education.

In the study, nearly 20% of people who didn't receive those services re-offended. For those who got those resources, the recidivism rate was 7.8%.

"We had one of the lowest incarceration rates in the country before 2018. But after 2018, it fell even further and sharper," Research Director at Mass. Inc. Ben Forman said.

Mass. Inc. is a public policy organization based in Beacon Hill that recently released a study looking at falling incarceration rates after 2018's sweeping criminal justice reform in Massachusetts.

"We found that most people who are going to prison in Massachusetts had been there several times before," Forman said. "It didn't take those first few times, so there was more crime and victimization happening, and there was heavy cost to the state. So, there was a lot of effort to look at how we could do a better job rehabilitating people who, come in contact with the criminal justice system."

The new approaches in the 2018 legislation included decriminalizing some minor offenses, reducing finds, expanding diversion programs for people with behavioral health issues, helping people return to their communities and more.

Forman said the changes have proven successful, with data to support that.

"Now we have, undisputed, the lowest incarceration rate in the United States," Forman said. "We also have significantly lower crime."

Nationally, the violent crime offense rate held steady from 2012 to 2022, according to FBI data. That was as the violent crime offense rate in Massachusetts dropped from 407 per 100,000 people — above the average — down to 322, far below the average.

A common theme across state agencies seems to be helping justice-impacted people, a term becoming more common in corrections, find tools they need to succeed.

Our effort to reduce incarceration, to provide more services to those who are incarcerated and put a lot of money into communities for prevention, for substance abuse treatment, mental health treatment, for workforce development and job training, all seem to be having, the desired outcome here," Forman said.

Like Ramos, Joanna Cataldo is in programming at the Haverhill Community Justice Support Center at the direction of the court. She said that she fell into drug use after the death of her mother around 20 years ago. But seven months ago, a judge sent her to the center.

"I was on the street running around doing drugs, getting in trouble," Cataldo said. "I'm 61-years-old, and I'm done. I'm done with the streets. I'm done with getting in trouble. And, like I said, this program saved my life."

Cataldo said that at the center, there's no shame. The therapy sessions and bonds she's formed have made her feel ready for a new chapter.

Vincent Lorenti, who oversees all of this through the Office of Community Corrections, said that the centers provide programming that balances support with accountability.

"The Community Justice Support Centers are a great opportunity to provide people, programing, treatment interventions like cognitive, behavioral interventions to address drug and alcohol use and also decision making, educational support," Lorenti said.

The Haverhill location celebrated its official grand opening at the end of March, where staff are ready to help dozens of clients at a time.

"We can use resources like what we have here, to keep to help people truly rehabilitate and rehabilitate, rather than again, placing people in secure facilities where, they're not maybe necessarily making the progress that they could make if they stayed in the community and kept those connections that they need to have in the community intact," Lorenti said.

Client just like Ramos, who's had time to self-reflect and work through trauma from his past — leaving him optimistic for his future.

"After this, I do see me going back into the community, doing motivational speaking, talking to people, talking to the youth and helping them navigate," Ramos said. "Because that's what I needed. And I would have wanted someone to help me. But now I got people to help me."

As the prison system is downsized, and more emphasis is placed on rehabilitation, Forman at Mass. Inc. hopes more money goes toward community resources, as well as mental health services.

He worries, though, that as the state budget tightens, recent investments and progress could face cuts.

"One of the questions that is out there is, are we going to peel back on some of that alternative spending that has allowed us to reduce incarceration without experiencing increases in crime," Forman said. "And those kinds of budget items are the ones that have often been cut disproportionately in tighter fiscal times."

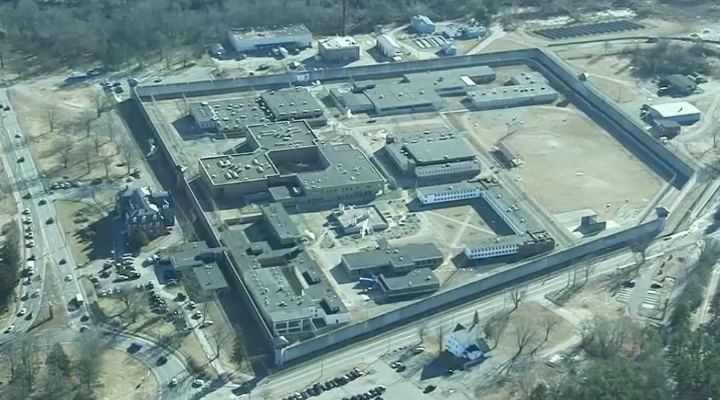

Speaking of money, the closing of MCI Concord is expected to save the state around $16 million per year, and also avoids nearly $200 million in capital projects that would have been needed to upkeep the aging prison.