Three mobile monoclonal antibody treatment clinics will open across Massachusetts for high-risk people who have been infected with or exposed to COVID-19, Gov. Charlie Baker announced Tuesday.

The treatment, which involves laboratory-produced molecules that can block COVID-19, has shown to be effective in reducing severity of disease and hospitalization.

WATCH ANYTIME FOR FREE

Stream NBC10 Boston news for free, 24/7, wherever you are. |

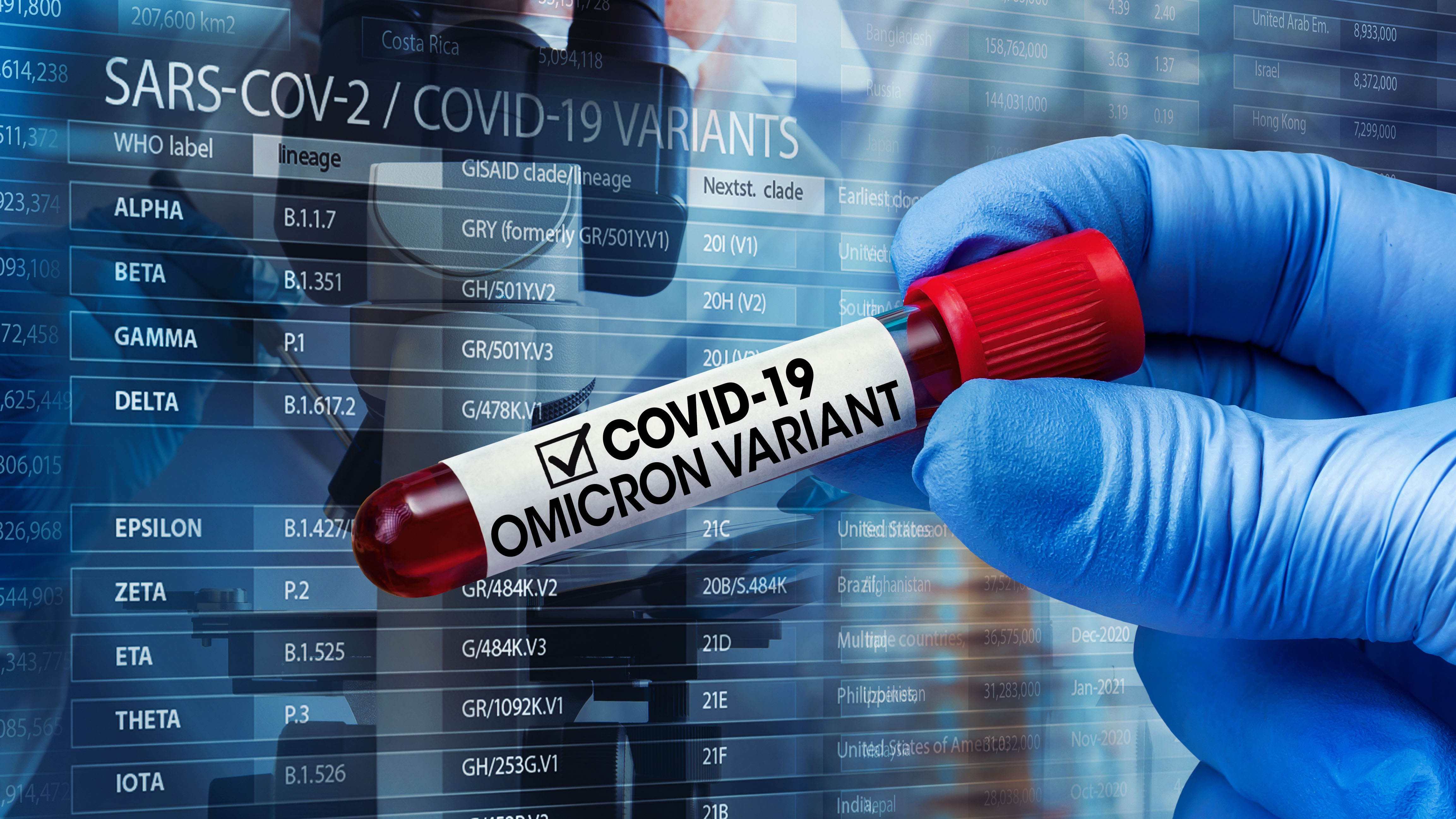

The expanded access to COVID-19 treatment comes amid mounting uncertainty around the new omicron variant of the coronavirus, first detected in southern Africa. The U.S. has yet to identify any cases, but the variant's transmissibility and potential to evade the protections afforded by vaccines has prompted warnings from experts both locally and nationally.

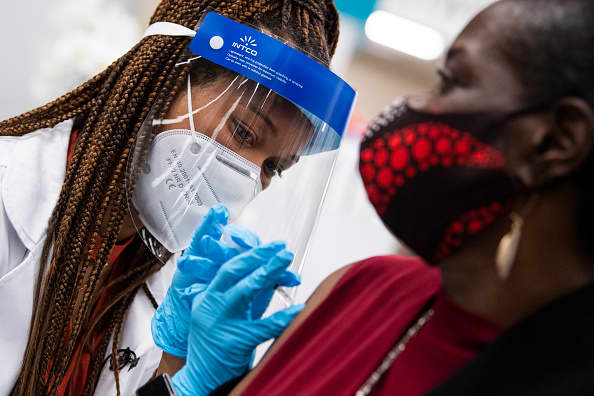

The new clinics have the capacity to treat a combined 500 patients per week. Patients are required to get a referral from their health care provider in order to receive the free treatment at any of the three new mobile clinics.

Get updates on what's happening in Boston to your inbox. Sign up for our News Headlines newsletter.

Sign up for our Breaking newsletter to get the most urgent news stories in your inbox.

The single intravenous infusion treatment takes 20 to 30 minutes, followed by an hour of patient monitoring. If administered within 10 days of the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, the one-time therapy is highly effective in neutralizing the virus and preventing symptoms from getting worse.

Anyone over the age of 12 who is high-risk and has tested positive for or been exposed to COVID-19 is eligible to get monoclonal antibody treatment, per the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorization.

Two of the mobile units, currently in Fall River and Holyoke, began administering monoclonal antibody treatment to patients on Nov. 22. A third unit will open in Everett on Dec. 3. The mobile clinic sites can be relocated easily based on demand, the Baker administration said.

More Coverage on Omicron

Mobile clinic staff will also be sent to treat people with monoclonal antibodies throughout the community, including in nursing homes, assisted living residences and congregate care settings.

With the addition of these three mobile units, there are now 32 locations across Massachusetts offering monoclonal antibody treatment. A map of sites can be found here.

“These mobile sites enable individuals with early COVID-19 or who have been exposed to COVID-19 to be treated quickly and safely with monoclonal antibody infusion,” Acting Public Health Commissioner Margret Cooke said. “While the best protection against COVID-19 is vaccination, these therapies can help prevent hospitalization and severe illness for infected or exposed high-risk individuals. People with questions about whether this treatment is right for them should discuss it with their healthcare provider.”

The temporary clinics will be operated by Gothams, a Texas-based emergency management company with experience supporting commercial, federal, and state facilities in COVID-19 emergency response, in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

What are monoclonal antibodies?

Dr. Daniel Kuritzkes, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital, explained what monoclonal antibodies are during the weekly "COVID Q&A" series earlier this month.

"They are antibodies that come from a single cell from somebody who has either been exposed to the coronavirus because of immunization or, more likely, because they have recovered from COVID-19," Kuritzkes explained. "And these cells make an antibody that is able to block the virus from entering. They attack the spike protein, the same protein that's in the vaccine."

The antibodies have shown that, if given very early, when people have symptoms but are not yet hospitalized, they can prevent people from progressing to the point of hospitalization.

"They've been less successful in people in the hospital, usually because by then people have their own antibodies," Kurizkes said.

However, Kurtizkes pointed to a number of studies that analyzed subsets of hospitalized patients who had not yet made their own antibodies showed that the monoclonal antibodies had a "dramatic effect" on survival.

"People were less likely to die if they got those antibodies," Kuritzkes.