Now that shark season is officially here, researchers on Cape Cod are busy trying to find a way to predict when the animals are swimming close to the shore.

They outlined their research at the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy Tuesday. They said most of the sharks are still being spotted on the outer Cape, where there is an abundance of seals. They also said sharks spend nearly half of their time in shallow waters that are less than 15 feet deep.

WATCH ANYTIME FOR FREE

Stream NBC10 Boston news for free, 24/7, wherever you are. |

The focus of their research is studying patterns in shark movements and eating habits to try and see how that translates public safety.

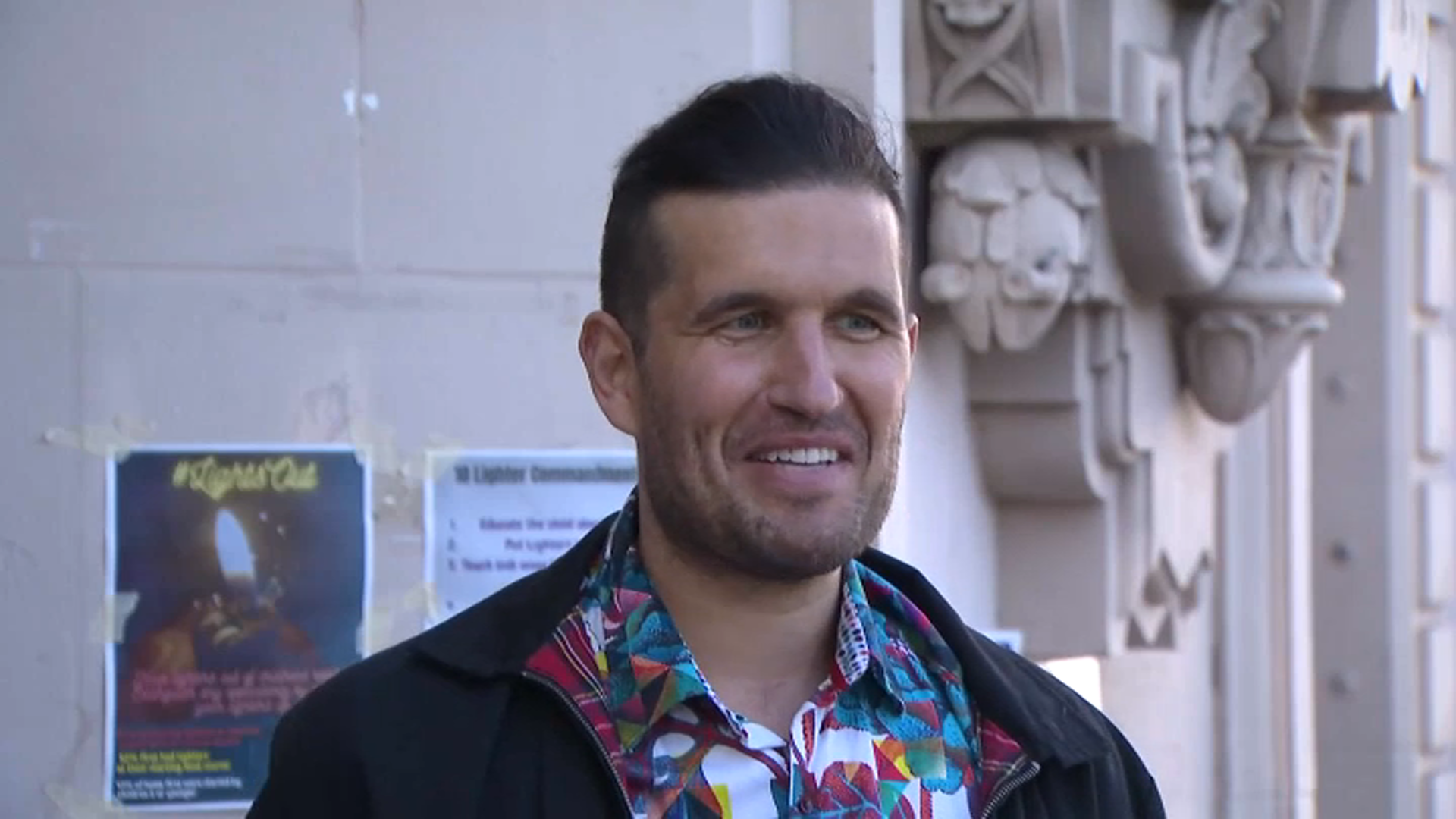

“If we see patterns in behavior that allow us to forecast where these animals will likely be in a certain area, then we can assist with public safety in terms of forecasting areas that might be more dangerous,” said top Massachusetts shark expert Greg Skomal.

Get updates on what's happening in Boston to your inbox. Sign up for our News Headlines newsletter.

Listen to our free podcast, "Shark Tales," which explores the world of sharks in New England with our partners at the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy. It's on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

They also went over the tools they are using to track the sharks, which includes real-time receivers and balloon-style cameras. They are putting two more receivers in the water at Newcomb Hollow and Head of the Meadow beaches this week, which brings the total to five.

When a tagged shark swims within 500 meters of a receiver, an alert is sent out to public safety officials, including lifeguards and beach managers, so they can tell swimmers to get out of the water.

Education is also a big priority, which is why the conservancy is also launching a shark smart program this summer.

“At the heart of all of this, it is really about people. We’re learning this information so we can provide it to the public and provide it to the people so they can modify their behavior to proactively reduce the risk of having a bad interaction with a great white,” researcher Megan Winton said.