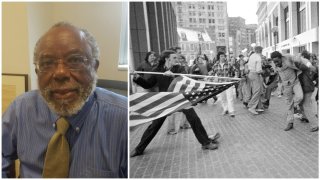

Millions of people have seen the iconic 1976 photograph of Ted Landsmark being attacked by anti-busing protesters on Boston City Hall Plaza, but few know him by name and most are unaware of his life as an educator and proponent of equal rights in Boston and beyond.

While Landsmark concedes he will be forever associated with the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo, he prefers to be recognized for his accomplishments as a community leader in Boston. In an odd twist, being at the center of one of the most significant civil rights photographs in history elevated Landsmark’s profile and gave him the chance to pursue social justice on behalf of many Bostonians.

“My life is determined by the mission that enabled me after that photograph was taken to articulate a set of values that are important within Boston and elsewhere,” Landsmark said. “To have so much of my life focused on just that one moment seems very ironic in the context of the other things that I’ve tried to do, not only in Boston, but around the country and in other parts of the world.”

More than 42 years after the attack, he remains acutely aware of the stigma associated with this city.

“There’s no question that Boston has a reputation for being a city that has been troubled by racial tensions for a long time, and that reputation obviously is a very negative one for the city in terms of how we feel about ourselves and how we want to be perceived as a welcoming city,” Landsmark said. ”Boston has its own problems, but they are America’s problems.”

He knows that when there’s a racial incident in Boston, it is magnified. Last summer when Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones said he was called the n-word by people in the stands at Fenway Park, across the country it appeared to be yet another, “Well, it’s Boston. What do you expect?” moment. The difference between 1977 and 2017, according to Landsmark, was the immediate response to Jones’ claim.

Local

In-depth news coverage of the Greater Boston Area.

“The Boston Red Sox, of their own volition, announced a series of steps that they were taking very seriously,” he said. “The Red Sox stepped up to say this is not acceptable in this venue.”

Landsmark, now 72 years old, has worked with three Boston mayors on public policy. He spent close to 20 years as the president of the Boston Architectural College and is currently the director at the Northeastern University’s Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy. All the while, he has dedicated his life to improving the lives of others.

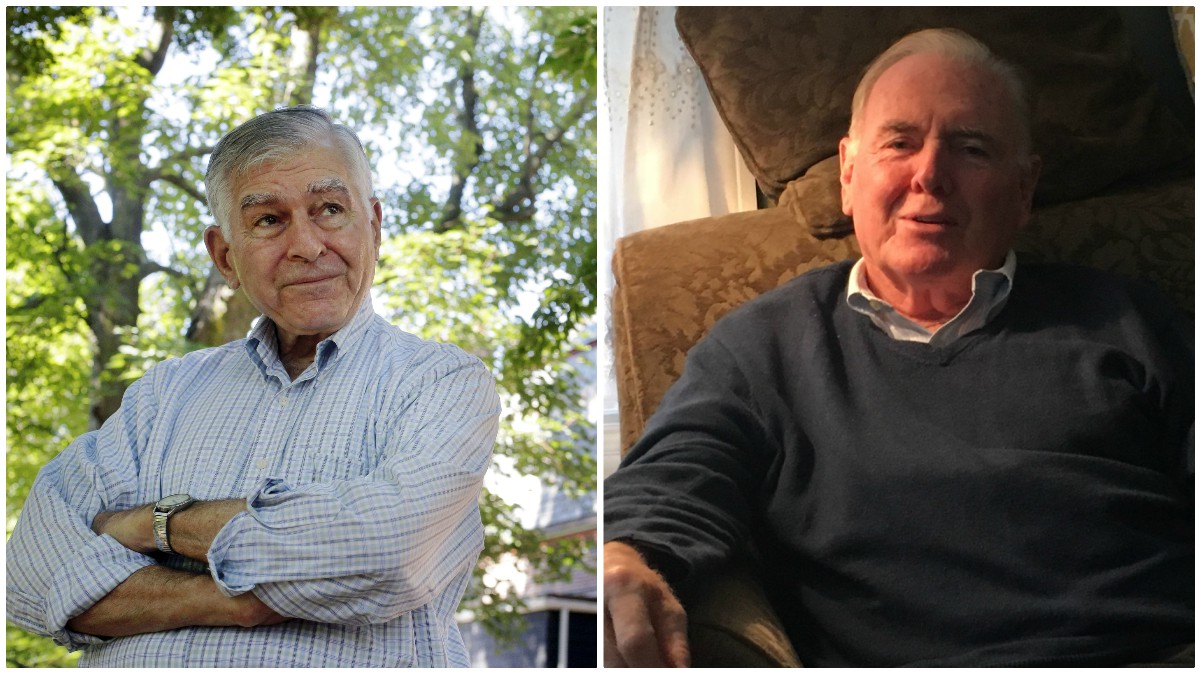

“When I got elected mayor of Boston I was anxious to recruit as many compassionate people from the African-American community into city hall and give them a strong voice in the issues affecting public policy in the city, and Ted was very good at that,” recalls former Boston Mayor Ray Flynn.

Landsmark worked in Flynn's administration as director of the Office of Jobs and Community Service, where he took on many initiatives, one of which was reducing the murder rate in Boston. Landsmark became one of Flynn's most trusted confidantes.

“He (Landsmark) was a team player, who obviously was very intelligent and he had this heart of fighting for the voiceless and the poor, that kind of deal. He didn’t have to shout out from the rooftops. You’d sit in the meetings with him in the room and you knew just darn well after everybody had their say he was going to emerge as a real calm, defining, insightful voice,” Flynn said. “I’d look over at him, and he knew what to do. He was the healer.”

Former Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis has known Landsmark since they both worked at Boston's Hill and Barlow law firm in the mid-1970s, prior to the Boston City Hall Plaza attack.

"Extraordinary young African-American man who came to this city, I assume with little or no connection to it, and has made, with others to be sure, made a really important contribution to this city’s evolution as a thoughtful, tolerant and very progressive community. He was one of a new generation that did that. And did so, remarkably, with little or no bias himself," Dukakis said. "Boston itself was trying to deal with some very, very, serious racial and religious issues."

If there was ever a person equipped to manage that episode on City Hall Plaza four decades ago, it was Landsmark. He simultaneously earned a law degree and a master’s degree in environmental design from Yale prior to moving to Boston in 1973. As a young man, he participated in civil rights demonstrations in Alabama, the March on Washington, and led an anti-Nazi rally as a high school student in New York.

“I had had the opportunity to be exposed to racial activities in the north and in the south, so I had some perspective on what it meant to be a victim of racial violence in Boston,” he said. “There was a moment that had come to me to step up and to be that thing that my past and my parents, and that people who had inspired me would have expected me to step up to do and to say.”

Landsmark’s pursuit of social justice was shaped by his family in New York City’s East Harlem neighborhood. They were second-generation West Indians who had previously established schools in the Caribbean. His aunt was a pianist who graduated from The Julliard School and his grandfather was a former whaling ship crew member who jumped ship in New Bedford around the time of the World War I German submarine attacks and became a coal yard worker and Garveyite in Harlem.

Landsmark recalls that his grandfather was a smart, politically active man who read The New York Times daily. In fact, Landsmark was born with the name Theodore Burrell and changed it to Theodore Landsmark prior to moving to Boston, in part to honor his grandfather who helped raise him. Landsmark’s mother was a nurse who later became a public school teacher, so from the time he was born he was surrounded by an air of political activism and academic achievement.

“There was a long-term commitment to education as a root for achieving social mobility and education as a way of broadening one’s perspective on the world,” he said. “There was always an expectation we would be involved in activities that were progressive and inclined toward outreach.”

As a teenager and Stuyvesant High School student in the 1960s, Landsmark exercised his activism in numerous demonstrations surrounding the civil rights and anti-war movements. He attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire and went on to Yale in 1964 to further his learning about social justice, majoring in political science and urban studies. During the anti-poverty initiatives at the time, Landsmark felt a calling to return home between his junior and senior years at college to work as a social worker and help young people get job training.

“I was feeling a little bit unmoored from where I’d grown up and what I knew and so I went back to East Harlem,” he said.

While at Yale, Landsmark continued his political activism as the chairman of the civil rights council. He traveled to the march in Selma, Alabama, with two white divinity students and along the way they had a memorable encounter at a segregated diner.

“We waited and waited and waited and we knew what was going on,” he said. “People moved away from us at the counter and finally, after a very, very extended period, the waitress behind the counter came up to us with tears in her eyes and said, ‘I’m sorry boys, but I just can’t do it.’ And we could tell if she served us, she would be at risk, so we left."

The three got back in their car and drove away from the diner, yet they were not in the clear. Someone in a pickup truck with a gun rack in the back window followed them out of town, which was particularly foreboding since it was shortly after civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman had been killed in the South.

Though he had yet to realize it, Landsmark was accumulating life experiences to prepare him for that fateful morning in 1976.

”I had done a lot of things prior to being attacked on City Hall Plaza that were about social justice and fairness and equity and I have done a lot of things since,” he said. “My life is determined by the mission that enabled me after that photograph was taken to articulate a set of values that are important within Boston and elsewhere.”

Despite my assurance that this story was to be about his perspective on race in Boston and his pursuit of social justice, and not simply a rehash of the City Hall Plaza incident, Landsmark initially balked when I asked about details of the attack.

“You know how many of these interviews I’ve had and then had them run and it was only about the guy from the 70’s who got attacked by the flag? You know, we’re not going there,” Landsmark said pointedly.

Eventually, he did go there.

When Landsmark moved to Boston in 1973, he was aware of the racial tension in the city. While a Yale undergrad, he remembers taking a class with education rights activist Jonathan Kozol, who had previously taught in the Boston public schools. Kozol had obtained tapes of Boston School Committee meetings and shared them with Landsmark’s college class.

“Elected members of the school committee were describing children of color as monkeys,” Landsmark said. “There were well-established patterns of racism directed against young people of color and communities of color in the city. So when I moved to Boston I was certainly aware of that.”

Boston was in the throes of a school busing crisis, which was creating a racial divide in the city. Despite the busing and integration initiatives throughout America, the Boston School Committee steadfastly wanted none of it.

Prior to the 1974 school year, Federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity said the Boston School Committee had deliberately engaged in school segregation and he mandated that students be bused between neighborhoods to alter the racial makeup of the city’s schools. The mandate involved busing students from South Boston, a historically white Irish area, and Roxbury, which was a predominantly black neighborhood. The decision lead to many violent protests and perpetuated the racial divide in the city.

“It was really such an ugly time. It wasn’t the city that I was proud of, that I could identify with," said Flynn.

While Landsmark was well aware of the busing crisis and racism in Boston, he said he felt isolated from the problems.

“I didn’t have any kids, so I thought, ‘Well, this doesn’t involve me, I just need to stay out of the way and do my job and I’ve only been here a couple of years and this is really unfortunate and I’m tired of having to apologize to all of my friends and family in New York about living in Boston,' but I couldn’t see that I had any direct engagement,” Landsmark said, “Even though periodically I would run into some idiot who would yell something racist at me, I thought, well, I’m young, I’m professional and I can deal with and overcome this and all of these other things that are happening in Boston.”

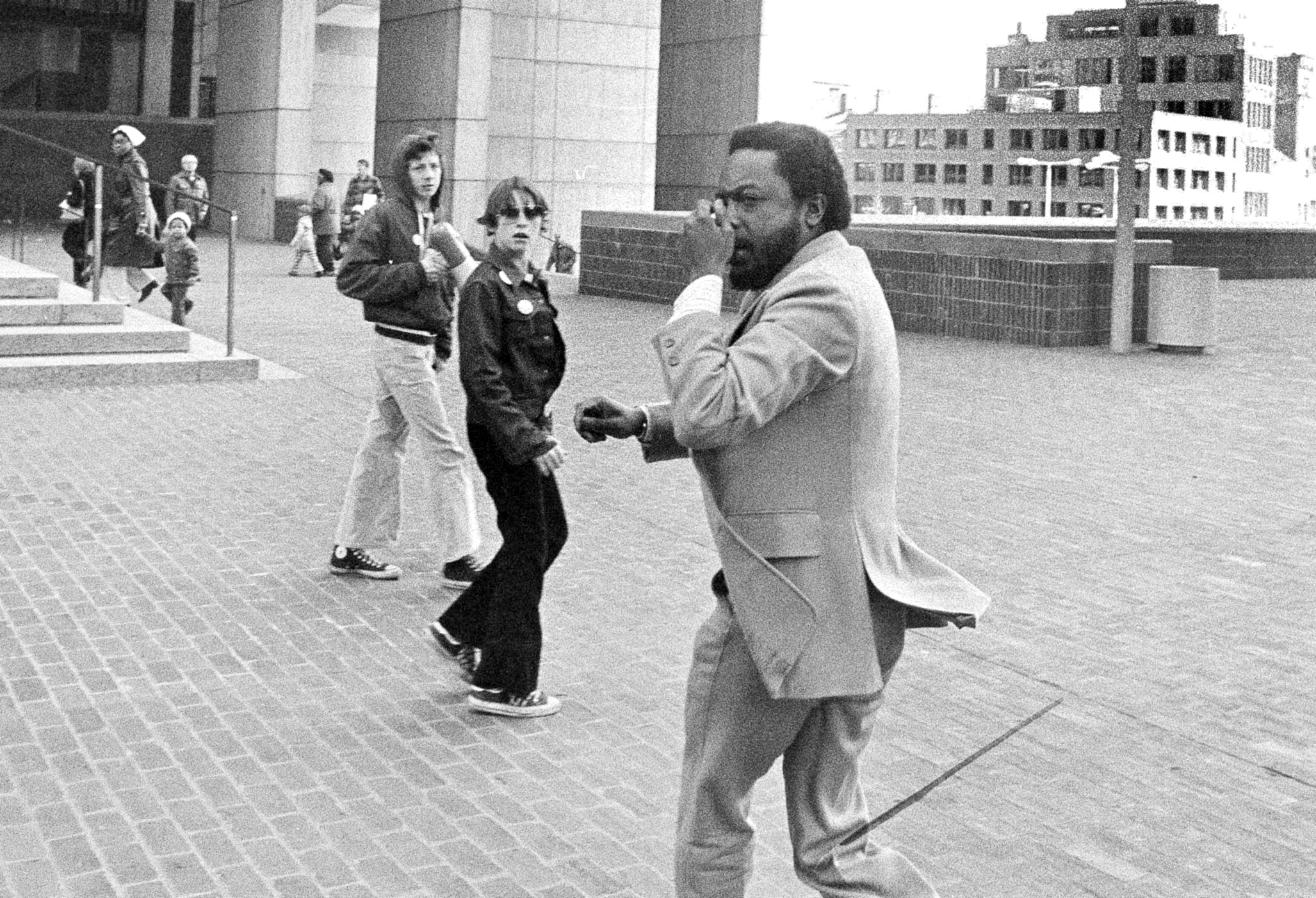

Landsmark was working as the director for the Contractors Association of Boston, a group seeking to get more local construction jobs for minorities. On the morning of April 5 he was on his way to a meeting at Boston City Hall and took a narrow passageway perpendicular to the city hall entrance. He couldn’t see what was happening around the corner.

When Landsmark turned the corner, he came upon approximately 100 high school students from South Boston and Charlestown coming towards him. The students were protesting school busing and had just gone to the office of City Council member Louise Day Hicks, a staunch opponent to desegregating the Boston schools.

“Several of the kids who had responded to being stirred up walked past me and then turned and came back to attack me,” he recalled.

He said they were shouting racial slurs, and one of the protesters punched him, knocking off his glasses and breaking his nose. As chaos ensued, another protester lunged at him with the American flag, but missed his mark.

In a flash, the group moved on to protest at Judge Garrity’s office a few blocks away. Landsmark was left soaked in blood, standing alone in front of City Hall.

There was a group of media covering the protest, and an Associated Press reporter ran to Landsmark and asked for his name and where he was going. The reporter then hurried off to cover the rest of the protest.

Seconds later, a police officer came to Landsmark's aid and told him that he had called for an ambulance. The officer grabbed Landsmark’s arm to help walk him to the pick-up point, however Landsmark did a quick assessment of the situation based on his experience in previous civil rights and anti-war demonstrations.

“I had an instinctive response that a white police officer holding the arm of a young black person was almost certainly to be interpreted as an arrest,” he said. “I had the presence of mind to say, ‘Wait a second, I think there are reporters here and if you’re holding my arm it’s going to look like you’re taking me into custody, so I’d appreciate if you let my arm go.”

The officer let Landsmark’s arm go and told him, “I guess you’re OK.”

Despite the flurry of events, from the time Landsmark turned the corner into the attack until the officer approached him, the entire episode lasted only about 45 seconds.

“On the way to the hospital, I had a few minutes to gather my thoughts to think, ‘Something weird has just happened to me and I think it was an anti-busing demonstration and I think somebody just tried to kill me with the American flag’.” Landsmark recalled with a laugh.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, Landsmark was admitted to the emergency room and the attending doctor told him that there were reporters outside who wanted to speak with him.

Landsmark recalls the doctor saying, “‘Your nose is broken and we can just snap it back into place and then you can go out and talk to these folks,’ and he pointed out that they could give me an anesthetic.” But the doctor also said that the anesthetic would likely cause drowsiness and slurred speech, which would affect Landsmark’s meeting with the reporters.

“So I said, ‘Just snap it back in,’ and maybe in the back of my mind I was thinking, ‘This is a moment when I have to be as lucid as possible.’”

Landsmark started thinking about addressing the reporters and thought back to a meeting during his college days with New York civil rights leader Whitney Young and the message Young delivered.

“A turning point in one’s life could come at any moment and that we’re not always prepared for that moment through our ability to speculate what we would do in that moment, but when the moment comes, be ready,” he thought.

Landsmark realized that his moment had come.

“I knew that that might be a turning point, not just for me personally, but for what was going on in Boston around the racial division that was taking place in the city,” Landsmark said. “I could either further inflame a very bad situation or I could say the kinds of things that would help to mobilize other people of conscience in the area who were looking for someone to give them the opportunity to express their own ethical feelings about racial injustice.”

Landsmark spoke to a small group of reporters outside the hospital, however, he and the rest of the world had yet to see the photograph of the attack that had been taken by Stanley Forman. The first time Landsmark became aware of the soon-to-be-iconic photo was when he received a telephone call from the Boston police detectives who had been working to identify the assailants and they wanted him to take a look at some contact sheets.

Landsmark had been a photojournalist in college and says upon seeing the photos at the police station he knew instantly that the photo of the student attacking him with the American flag was sure to resonate around the world.

“That evening I saw the photograph, which then went out on the wire services, along with the story, which showed up in national and international media within 24 to 48 hours, and at that point I had to go into hiding with a friend because I was deluged with media and also friends and also some death threats,” Landsmark said.

Upon seeing the photo, Landsmark said he called his mother to alert her to be aware of the photo before she saw it in the New York papers.

“I knew that event would generate substantial international publicity, in part because of the photograph, and in part because the event itself was just so dramatic and I felt that it was important for me to speak beyond myself and not to indulge in a kind of personal response to the photo, but really to take that moment as a moment to speak to a wider audience that needed to become engaged in the issues in a way where people who were in a position to address the racism in Boston,” he said.

“I was appalled. I mean, God, I knew him, thought highly of him, knew what he was doing, how committed he was to social justice and to a just society," Dukakis said of his thoughts upon first seeing the photo." "It was appalling and at the same time, sadly for us in this area, it said a lot about us and what we were doing and what we weren’t doing. And that was a tough period. “

Landsmark took the stage at a much larger news conference two days after the incident. The event was recorded and still exists online, but more than 40 years later, he has yet to watch it because he said it’s “too emotionally traumatizing.”

The gathering of more than 100 people was attended by local and national media, as well as an array of black political activists from Boston. It was at that time Landsmark once again channeled the wisdom of Whitney Young.

“You never know what you’re really being prepared for as you go through certain kinds of experiences, but when the moment comes, you need to assemble all of the experiences you’ve had to focus on that moment to do and to say the right thing,” Landsmark said. “It was a responsibility that I had to speak for those many people who had suffered and had worked so hard to be equal in this city and it was my moment to speak for them.“

So, in a crowded room with people curious and anxious to hear from the victim at the center of the photograph seen around the world, Landsmark, still with bandages covering his entire face, delivered his message.

“We must avoid being exploited and having this act of violence exploited to distract attention from the complex and extremely urgent problem of the life of this city and the lives of black and white people and all colored peoples in this city. Safety is not the issue. Busing is not the issue. The issue involves the participation of citizens of color in all levels of business and government that affect the life of this city. By that I mean participation on equal basis, and not just as human rights officers and affirmative action officers and not just as shields to cover the white power structure’s indifference towards communities of color,” Landsmark told the crowd. “While I have been hurt and wronged personally by the attack, it is people of color and humanity everywhere who will benefit from satisfactory resolution of Boston’s problems.”

That news conference marked the point when Landsmark became a catalyst for healing the racial wounds in Boston by leveraging the interest in him to perpetuate his pursuit of social justice.

“He didn’t exploit the situation. Some people have an inclination to want to seize on an opportunity, poor-mouth the situation, but Ted Landsmark didn’t do that. He was firm and he was strong and he was uncompromising, but he was still a uniter. That’s what the city needed," Flynn said. “He almost became the face of the challenge of what needed to be done. We saw the worst, now our job was to make it the best. When you think about it, that’s exactly what happened."

And while Landsmark still bristles at the notion that he is defined by his image in the photo on City Hall Plaza, he does concede that the events of April 5, 1976 gave him new avenues to pursue social justice.

“Mel King, who was then an elected state representative, brought a group of people together to meet in local churches and places of faith to talk about ethics and race and economic opportunity. We had opportunities to meet with heads of local corporations to talk about increasing employment opportunities for people of color in the city. We had opportunities to bring cultural groups together to talk about their relative silence up to that point and the responsibility that they had as cultural institutions to step up,” Landsmark said. “We talked to public agencies, including the transit agencies and many of the state agencies about the fact that many of them did not have in place programs that encouraged or incentivized the hiring of people of color across the board. What followed were many months of useful and very open discussions that began to open up educational and job opportunities for people of color in Boston that had not existed prior to that.”

“To see how a young African-American with a lot of intelligence and a lot of courage was able to emerge as a leader and as a role model in this city — he was one of a new generation that did that,” Dukakis recalled. "And did so, remarkably, with little or no bias himself. How they put up with that stuff and didn’t become hateful themselves is a miracle of sorts.”

I sit with Landsmark in his office at Northeastern and discuss social justice and how it exists in today’s Boston. By his definition, it’s the ability to be treated fairly without regard to race, origin, gender, sexual orientation, age, or disability. Landsmark says life for most Bostonians has improved significantly and most residents in the city are living better now than they were several decades ago. However, he does caution that data suggests Boston has actually declined in terms of fairness due to the erosion of the middle class.

“There’s been a fragmentation of society in Boston that has created greater social and cultural differences in the city,” Landsmark said. “A city needs a thriving middle class in order to build a real sense of community, lest low wage earners feel there’s no upward mobility for them and wealthy people feel that there’s no need for them to show any sense of caring or of commitment towards people who earn less than they do. And as long as there is an upper class that feels that it has no real commitment to the future of the city, then the city’s infrastructure fragments and the sense of community is diminished.”

Last year, the Boston Globe published a Spotlight series on race in Boston, and despite the progress that has been made toward mitigating racism in this city, the report cited some glaring realities and perceptions.

The median net worth, what is owned minus what is owed, for African-American households is just $8, compared to white households with a median net worth of $247,500. A poll showed 54 percent of black people across the country rated Boston as unwelcoming to people of color, far more than cities like New York, Atlanta, and San Francisco. Landsmark says part of the problem is the inability to assimilate people of color into positions of real power and authority in Boston.

“One looks at corporations, universities, major hospitals, some public entities, still one does not see highly qualified people of color,” Landsmark said. “One does not see a clear way for a young person in the city to climb a ladder of opportunity that’s going to place them in a leadership position.”

Outside of Boston, due in part to the 1976 attack photo, the city’s racial climate has been fodder for commentators and comedians. On the eve of the 2017 Super Bowl between the Patriots and Falcons, Saturday Night Live’s Michael Che referred to Boston as “the most racist city he’s ever been to.” In the 2018 Saturday Night Live season premiere, actor Adam Driver was in a skit about the “League of the South,” where attendees discuss the virtues of living in neo-confederate America. Driver continually tells the group that Vermont has all the things they’re seeking and when the leader asks him if he’s new in town, Driver tells him he’s from, “up north.” The leader is aghast at a liberal Yankee in the neo-confederate crowd, but Driver cuts him off and says, “ Don’t worry. I’m from Boston.” The leader responds, “Alright, good, good,” as the audience laughs.

In September, Comedy Central's The Daily Show aired a segment entitled, "How Racist is Boston?" Roy Wood Jr. interviews Boston Globe reporters who worked on the Spotlight series on race in Boston, as well as black and white residents. Veiled in humor, Wood Jr. addresses Boston's history of racism, including the Red Sox being the last team to integrate, the anti-busing era, and even the Adam Jones incident.

While Landsmark acknowledges there are still racial problems in Boston, he is quick to point out that every major city in America has encountered some level of difficulty with law enforcement, fair housing, employment practices, and education, in the last decades. He adds that more than 80 percent of Boston’s current residents did not live here during busing or during the 1970’s.

“In the 1970’s Boston was perceived to be a bifurcated city, racially. Relationships were viewed as black-white relationships. Today the city is much more diverse and different sets of political and cultural coalitions have come together to address questions and issues of culture and race and economics and class,” Landsmark said. “There are more diverse people of color on the Boston City Council today than there were in 1976 and the immigrant population into Boston has brought a different kind of richness of political expectation on the part of people who live here, vote here and work here.”

That Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph shed light on the racial difficulties in Boston during America's bicentennial year, and it also gave Landsmark the opportunity to spontaneously turn from a victim into a force for social justice in this city.

Flynn saw that transformation first-hand. At his South Boston home, adorned with photos of him posing with world-famous humanitarians like Coretta Scott King and Nelson Mandella, Flynn gives Landsmark high praise for his leadership and contribution to Boston's healing.

“I happened to deal with him in City Hall, but you could have easily put him in the White House and he would have had the same role to play. I’ve worked with Popes and presidents and prime ministers there over the last 50 years and I’ve seen some of the best people,” Flynn said. “Ted would be up there with some of them."

“I knew and understood you don’t get to retract a bad or foolish statement and I think that that’s particularly salient now in the era of social media and so you need to be prepared to act responsibly in the moment, “ Landsmark said.

A turning point in one’s life could come at any moment. When the moment came for Ted Landsmark, he was ready.