A winter seasonal forecast: entertainment or science? The truth lies somewhere in between.

Though there are those who’ve devoted their entire professional lives to the study of seasonal prediction, those of us in the sector of broadcast meteorology are jacks of all trades, forecasting daily weather predictions and, for the brave, trying our hand at seasonal forecasting, as well.

Of course, there’s a middle ground: the monthly forecast you see from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m. on the first weekday of each new month finds a happy medium between our 10-day forecast. That prediction is met with as little as a six degree error at Day 10, depending on the season – and a seasonal forecast, for which even those who devote their lives to constructing find a success rate better than a coin flip, but not always: on average, about a 40% improvement over a random guess.

Yet, whether it’s from the government, the Farmer’s Almanac or Old Farmer’s Almanac, a media outlet or an otherwise unknown social media account unsuspecting internet users happen upon, we as a society seemingly can’t get enough of gazing into a murky crystal ball to see exactly what pains the next winter will hold for us.

For exactly that reason, meteorologists representing all of our NBC owned stations in the Northeast met virtually for the second year in a row to brainstorm forecast thoughts for the upcoming Winter of 2020-2021 – and you might be surprised at where we landed.

The conversation started with an acknowledgement that winter is no longer what it used to be. For the last several years in the continental United States and particularly the East Coast, when it comes to snow and winter cold, you’re either in it, or you’re not.

Weather Stories

We’ve seen this unfold in several ways: the now-famous “polar vortex” delivering intense bursts of dramatic cold; the record-shattering winter of 2015 here in New England where our seasonal snow record was broken in two months after a lackluster start to winter; stretches where winter is seemingly absent and replaced by mild spells and a snow drought; entire winter seasons that pass without much in the way of meaningful snow.

There is an unquestionable link to a changing climate in all of these signals – even the cold and snowy ones. As the atmosphere warms, the tried and true pattern of polar cold north and warmer air south breaks down. Instead, we find warming in high levels of the atmosphere dislodging cold near the ground, sending it in fractured pools southward as surges of intense, exceptional, but relatively localized cold.

We’ve found warmer-than-normal conditions surrounding these break-away cold domes and, where the cold surges and abundant warmth collide, we find snow. Lots of it. This virtually guarantees that each year there will be at least a few zones globally that find incredibly snowy winters with shots of remarkable cold – but all of that is happening on a backdrop of a warming climate.

So, as our NBC meteorologists from across the Northeast made note of these observations, we also turned to some of our own who have devoted vast chunks of their lives to researching historical patterns and trying to draw connections from what once was to what is yet to be.

Glenn “Hurricane” Schwartz at NBC10 in Philadelphia annually combs over encyclopedic volumes of historical data to find perfect matches to the current impending winter pattern, referencing our recent seasons. NBC Washington’s Doug Kammerer, after years of exchanging ideas with Glenn in Philly, takes a similar approach with his own flair, examining “teleconnections” that tie weather in one part of the globe to weather in another.

As for yours truly, I weigh heavily the effects of ocean/atmosphere interaction, working to take clues from the jet stream pattern’s response to those interactions in the months leading up.

Here’s what we all determined: winter is not what it used to be. Climate change has not only changed weather patterns, but has also changed the game. In recent years, you simply cannot look back decades ago, find a match and expect to see a similar winter play out. For all the reasons mentioned above, there are new factors that disrupt and disjoint what was once a fairly stable regime in our atmosphere. With all of this considered, it becomes less surprising that the winter of 2018-19 found the experts at the Climate Prediction Center trying to explain “negative skill” for the first time in a long time: a winter forecast that actually performed worse than a random guess.

So where does this leave New England? Where does this leave any region when it comes to winter forecasts? It depends how honest we want to be, but one thing that is true of the vast majority of our NBC owned station meteorologists: we aren’t afraid to be honest. The honest answer, in our collective estimate, is the stakes are tremendously high in winter forecasting now, because you’re trying to nail down wobbling surges of fractured cold and interactions with sustained warmth…and being off by a couple dozen miles – a virtual pinpoint in the world of meteorology – can make all the difference between warmth and little snow, to warmth and lots of snow, or cold and varying amounts of snow. There are, however, still clues…

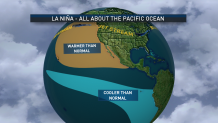

This year we’ve seen a pronounced “La Nina” pattern in the Pacific Ocean. The tell-tale sign of a La Nina pattern in the Pacific Ocean is colder-than-normal ocean water temperatures near the equator, extending west from the coast of South America. This classic calling card of La Nina is clear this season (this is, by the way, the opposite of El Nino, which consists of warmer-than-normal ocean temperatures in the same region of the Equatorial Pacific Ocean). Because of the basic laws of physics, a change in ocean temperature prompts a change in air temperature. A change in temperature results in a change in pressure. A change in pressure results in a change in wind patterns. There is no wind more important in predicting weather in the United States than the “Westerlies” – the jet stream – the fast river of air, high in the sky, that steers storms and acts as a boundary between cold air to the north and warm to the south.

The long and short of such pressure and wind changes in a La Nina pattern is to carry an active jet stream high across the Eastern Pacific and into the Pacific Northwest, opening the door for relatively mild air to flood the United States from west to east on the south side of and along the jet stream, and delivering an active storm path laden with Pacific moisture into the Pacific Northwest. Although incursions of cold from western and central Canada can occasionally intrude southward anywhere from the Great Lakes to the Northeast in this pattern, overall warmth usually is able to dominate in the Northeast, as well.

Now, adjust for climate change: make the warm warmer, make the cold more regionalized but more intense. This leaves you with a three-pronged solution: the vast majority of the United States will likely be warmer than normal, much of the northern half of the country near the jet stream will be wetter than normal with Pacific moisture inherent in each disturbance, but wherever the battle between that warmth and fractured cold unfolds…mega snow has the potential to dump. So where will that clash set up this year?

Evaluating the past several years of averaged surface temperature shows meaningful cold surges with staying power have trouble making it south of the Northern Tier of the United States…with the warm, La Nina pattern, there’s absolutely no reason to bank on that happening this year at all. That’s not to say it’ll never get cold farther south, rather…it’s just going to be hard to get it to last at all. Additionally, the influx of Pacific warmth makes it very unlikely for these surges to penetrate into the western United States this winter, either. This means substantial cold outbreaks should either stay in central and eastern Canada, or migrate southward somewhere between the Upper Great Lakes and Northeast.

In reality, the answer is likely to be both…cold with staying power will largely stay in central and eastern Canada, unable to dislodge abundant warmth in the long term in the eastern United States, but the occasional incursions of penetrating cold – the “polar vortex” breakaways that used to be bona fide, large masses of cold – will fire south across Hudson Bay in Canada and occasionally into the eastern Great Lakes and New England, finding an inherent weakness between the jet stream “ridge,” or northern extrusion of the jet stream, over the warm North Atlantic, and the counterpart ridge over the Eastern Pacific to the eastern United States.

In summary, this leaves the upper Great Lakes to northern New England as the best chances for temperatures near normal over the winter, as the abundant warmth does battle with the vestiges of meaningful cold…with much of the rest of the nation warmer-than-normal, overall, for the winter. Precipitation – snow, mix and rain – would be plentiful in the central and northern United States owing to the active jet stream and frequent doses of Pacific-initiated moisture, helping to continue a slow alleviation of the drought in these regions while the southern tier of the nation sees a much drier than normal winter, which may not only exacerbate spring wildfires in Florida but could get things going during the winter there.

As for snow – it’s going to be hard for much of the country to reach or exceed normal in this type of pattern, but in maintaining perspective it’s critical to note that one blockbuster storm feeding off an exceptional southward surge of cold air could deliver near or above average snow the farther south one is, but on the whole, a widespread snowy pattern just isn’t likely for most of the country.

The exception will be those areas that sit on the southern edge of the cold – the upper Great Lakes, eastern Great Lakes through northern New York and into northern New England. Keep in mind the way of the climate-changed winter: where it snows, it dumps. If the jet stream and corresponding temperature pattern plays out as I’ve laid out above, this puts these areas on guard for heavy snow seasons along with Minneapolis, Detroit, Buffalo and Albany to Burlington, Vermont, the ski and snowmobile country of New England, and much of central and northern Maine.

It also puts Chicago, Cleveland, and Boston just south of this zone: keep in mind, in modern winters, just south seems to be too far south, but certainly puts this corridor in the game for bigger snows when the stronger surges of cold invade, and perhaps, moreover, for several events of snow changing to sleet and freezing rain, particularly away from the coast where warmth from the south would be quick to ride overhead but dense shots of cold air would be stubborn to relinquish control at ground-level.

Put all of this together for New England and you’re left with: above normal snow in northern New England, near-normal snow in central New England, below normal snow in southern New England (especially the Massachusetts Turnpike and southward). Above normal temperatures for most of the region, but the chance for near-normal temperatures in the North Country owing to shots of more meaningful cold.

Of course, with our winters agreed upon by our NBC meteorologists to be in somewhat uncharted territory since a changing climate has started really flexing its muscle in the fifteen years or so, we all came to a resounding agreement: monthly forecasts like the one you see on NBC10 Boston and NECN are by far the better, most trustworthy way to go.

So, while this is a best estimate on the winter, check back on that first weekday of each month…and frankly, every day: as you can probably tell, this is a passion for our team and we’ll be keeping you posted as the biggest forecasting challenge of all – the winter season – shows its hand.